In the attic of a Nazi concentration camp, a hidden radio crackled to life – and Winston Churchill’s voice filled the air.

He was announcing the end of war in Europe and Beatrix Frank was the first person in the Theresienstadt camp in Czechoslovakia to hear those famous words.

She quickly spread news of Germany’s surrender 80 years ago today, but her fellow inmates did not share her hope or optimism. Instead they were filled with fear and dread.

Her son, Steven, was just nine at the time and he was on death’s door, starving and fighting an infestation of worms in his gut.

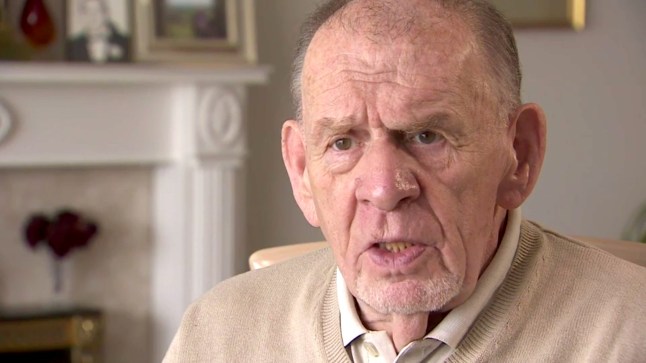

Now 89, he told Metro: ‘We were still under German occupation and people were terrified of what the Germans were going to do before the war ended that night.

‘We thought they were going to get rid of as many Jews as they could before midnight.’

Beatrix lived with Steven and his brothers, Nick and Carrel, in the Theresienstadt ghetto and transit camp since September 1944.

Although Beatrix was from England, the Dutch-Jewish family had been living in Amsterdam where Steven’s father, Leonard, was in the resistance.

After he was betrayed and sent to Auschwitz, Beatrix and her sons ended up in a string of camps before arriving at Theresienstadt – a holding pen and ghetto designed to kill as many Jews as possible.

Steven said: ‘People were dying all over the place. Starvation was rampant. There was little food about.’

He and his brothers only survived thanks to Beatrix being able to claim extra rations by working in the camp’s hospital laundry.

It meant they were well enough to notice that the end of the war was fast approaching.

Steven said: ‘The turning point was when the planes going overhead did not have black crosses on their wings.

‘They were white stars, which were American planes, not German. We began to realize that something was changing.’

In 1945, on what we now call VE Day, Steven’s mum heard the news thousands of prisoners had been waiting for.

She was approached by Russian inmates who took her to a radio they had hidden in their attic.

Steven said: ‘They knew something important was going to be broadcast, but it was going to be in English.

‘So they asked my mother if she would listen to it, and they took her up in the attic, and they gave her a piece of paper with a pencil.

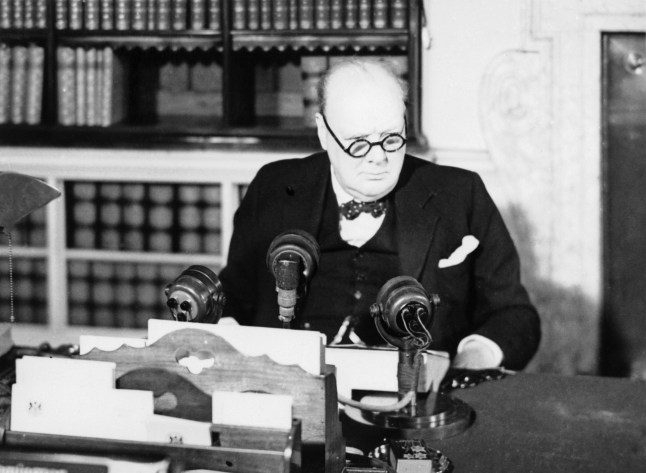

‘So my mother listened, and it was Winston Churchill broadcasting over the overseas service of the BBC from the Cabinet War Rooms.

‘My mother was probably the very first person in the camp to realise that at midnight, the war would be over.’

Steven, who was in a children’s home in the camp, soon learned the news of Germany’s surrender. Then came the rumours that Germany was about to destroy the camp and kill everyone.

He said: ‘The Germans absolutely hated us. They were building the gas chambers in Theresienstadt.

‘There had even been a rumour that they dynamited the camp. It felt touch and go whether the war was going to end before we were going to die.’

But when the camp woke up on May 9, the Soviet Red Army were at the gates and liberated Theresienstadt.

He said: ‘There was a sigh of relief that the threat of death, the threat of deportation, the threat of being gassed was now over.

‘But then somehow or other we had to try and keep living. People were quietly happy but determined to try to keep alive.’

In the months that followed, the Franks embarked on a remarkable journey through Europe to get to London, where Beatrix’s family lived.

She begged the Red Cross not to take them back to Holland, where she feared all her family were dead.

They then talked their way onto a British plane at the Czech city of Pilsen, and again managed to get a flight to London from Paris.

It was there, after driving through the Blitz-destroyed London, that Beatrix reunited with her father and began a new life with her children in England.

Steven said: ‘It was an extraordinary journey and tremendous ingenuity and determination by my mum.

‘VE day, of course, has always been very important to me because it’s about veterans. If it wasn’t for them we wouldn’t be here today.’

While Steven’s family struggled in Theresienstadt, another young boy had narrowly escaped the Nazis six years earlier on a doomed voyage across the Atlantic.

Gerald Granston left a German port heading to Cuba, but in a twist that saved his life, ended up in England.

He was on the infamous SS St Louis, a German ship filled with Jewish refugees that nobody wanted.

By the time it departed Hamburg on May 13, 1939, Gerald and his father, Heinz, had survived devastating Nazi persecution in their home town in Eastern Germany.

Their synagogue had been destroyed during Kristallnacht, the destructive night of attacks against Jewish people in 1938.

Gerald, who was six when he boarded the St Louis, told Metro: ‘Kristallnacht was a catalyst. The synagogue was totally trashed. It was obvious, even as a six-year-old, that it was state prejudice.

‘I was told that when I walked past a policeman, I had to walk in the gutter and not look at him.’

It is no surprise, then, that the mood inside the SS St Louis was jubilant as Gerald, his father and 900 other Jewish refugees sailed away from Germany to Cuba.

Gerald said: ‘Even at six I could see my father smiling again. The ship was magnificent. I had never had life like it for two weeks.

‘The sailors would tell us: “When you get to Cuba, you’ll love it”.’

Cuba was seen as a transit point to get to America, the promise of safety that all Jewish refugees had paid thousands to try to reach.

But as the ship pulled up outside the Caribbean Island, there was a problem: Cuba didn’t want them.

Officials refused to let the refugees off the ship, despite a week of haggling, and US officials in Florida did the same days later.

So the ship had no option but to turn back and head to Europe.

Gerald remembered the horror on board: ‘Everything changed on the way back.

‘Even I knew that wasn’t good. I saw people crying their eyes out, saying “we are going back to Germany”.’

In the end, the ship’s passengers did not have to go back to Nazi Germany, as Belgium, France, Holland and the UK agreed to take the refugees.

Gerald and his dad arrived in London in June 1939. They were two of the 288 passengers taken in by the UK.

They were the lucky ones – 250 of the other passengers died at the hands of the Nazis as Hitler’s war machine conquered the whole of Europe in the years to come.

Hardship was not over for them either, as Gerald was twice evacuated to avoid the horrors of the Blitz in London.

But he was in the capital to experience one of London’s most memorable moments – the rapturous celebrations for VE Day 1945.

Gerald added: ‘I went along with a family friend. We got on the underground from West Hampstead and travelled to Baker Street.

‘We wanted to go to the Mall, but people were going mad.

‘I remember trying to climb up a pedestrian crossing. Their lights were flashing on and off.

‘It was a feeling I’d never felt again. The Germans were beaten.’

As Gerald was jubilant on that day, he was all but unaware of the scale of the horrors faced by other Jewish people who were trapped in Europe.

Six million Jewish people, as well as another five million who weren’t, were killed at concentration camps, in ghettos or at the hands of German officers during the Holocaust.

Both Steven and Gerald have made it their life’s mission to educate others, in particular children, about Nazi’s Germany persecutions of Jewish people and other minorities through their own stories.

The pair have both been awarded British Empire Medals for these efforts.

Steven, who has given close to 1,000 talks in schools, told Metro: ‘It’s my thank you to this country for having allowed me to come here, to live here, and brought up here, and to love here, and to bring my family up in this country.’

Source: metro.co.uk